For the audio version of this essay, click below!

After that title, you might expect to launch straight into the culture wars: presidential edict on gender, who should be allowed to play on which sports teams, all of that!

But, no. This begins at the beginning, with cell division.

Wait, though! Before you groan and navigate away, let me assure you that this really is the best way to understand what’s going on. And I’ll try my best to keep the biology from being boring.

#

So, a cell. The smallest sort of living thing that there can be. Since it’s living, it’s going to take in energy from its surroundings, use that energy to grow, and eventually make more copies of itself. That’s what it means to be alive. A chaos-causing, world-eating self-replication machine. Whether we’re talking about you or me or a frog or algae or a bacterium, that’s what life does.

And if we’re considering only organisms that happen to live here on the planet Earth, then inside that cell, there’s going to be a genome – a set of instructions for making itself into a living thing – that’s encoded by a molecule called a nucleic acid. You probably know this by its abbreviation: DNA. This sort of molecule is kind of cool, because it contains information – it’s written in a 4-letter code, which is more efficient than the binary code used in telephones & computers – and because it can be copied.

The information has all the instructions for making a living thing, usually written in a procedural sort of shorthand – in this sort of situation, do that – which is why so many living things make patterns, like why twigs and lungs and blood vessels all look like miniature trees. These systems work because various chemical signals dim as the thing grows, and the DNA instruction will say something like “once this chemical signal dims by half, it’s time to branch again.”

And the sorts of DNA instructions that still exist in the world – that we might find if we were to read the DNA inside your cells, or the DNA inside a contemporary bacterium that’s stuck to the bottom of your shoe – those DNA instructions make organisms that are good at persisting. Good at surviving and making copies of themselves. Otherwise, the instructions wouldn’t still be here. If an organism weren’t good at getting energy and growing and copying itself, then its lineage probably would have disappeared.

Well, mostly. Everything that’s currently in the world is descended from things that were good at existing and copying themselves. That’s how we got the present world. We were copied from instructions that were successful in the past. But it’s unclear what the future will bring.

Pandas are made from instructions that were pretty successful in the past! But it seems unlikely that future pandas will inherit the earth.

#

A cell has instructions for being, and those instructions are written in DNA. Which means that its most important instructions will specify how to copy its DNA. Because if there are ever going to be two cells like this, each cell is going to need its own full set of all those DNA instructions!

DNA is written in a 4-letter code, and DNA is stored as a “double helix.” In addition to the all the instructions for making a cell, there’s an equal amount of shadow text that’s gibberish. If we imagine a code where each of the 26 letters of the English alphabet is paired with a partner from the other end, like A:Z, B:Y, C:X, D:W, and so on, then if a cell was going to store the instruction:

“PET THE DOG NOW”

It would store that information in a double helix, where only one side contains information that makes any sense when we try to read it:

PET THE DOG NOW

KVG GSV WLT MLD

That second set of “information” looks useless – I have no idea what “KVG GSV WLT MLD” is supposed to mean!!!? – except that it can be used to restore the useful message, as long as you apply the right code:

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Z Y X W V U T S R Q P O N M L K J I H G F E D C B A

And this means you can split the double helix into two separate strands of information, then apply the code and turn each half back into a full double helix. Each of the two new double helices will have both the useful message and the supporting gibberish.

For DNA, the code has fewer letters:

A G C T

T C G A

Every time there’s an A in a message in DNA, the supporting gibberish will have a matching T. Every time there’s a C, the supporting gibberish will have a G.

If we have a single-celled organism, it grows for a while, copies all its DNA, then splits into two. Which results in two nearly identical organisms, each with all the original DNA instructions. And those two cells can carry on, each growing and copying their DNA and then splitting into two again, soon making four, then eight, then sixteen, and thereby filling up the world! Huzzah! Our industrious little cell is winning!

#

When a cell copies its DNA, it sometimes make mistakes. Not often. If the DNA in one of your cells is being copied, the letter T will be paired with the letter A something like nine hundred and ninety nine million, nine hundred and ninety nine thousand, nine hundred and ninety nine times out of a billion.1

Which seems pretty impressive to me: they’re just little cells! And yet, they only make mistakes about once in a billion? I had to check my work twice to be sure that I didn’t goof with my “PET THE DOG NOW / KVG GSV WLT MLD” pairing, and that was only twelve letters long! There would be so many mistakes if I sat here and tried to transcribe a set of instructions that used billions of characters!

Still, even though cells are pretty great at copying DNA, sometimes there will be an A in one strand of the double helix and a cell will pair it with a letter other than T while copying it. That’s a mutation. Or sometimes the cell will lose its place and accidentally include a whole big section twice. That’s another type of mutation. This doesn’t happen often. But one in a billion isn’t zero.

Your own genome is about 6 billion letters long – every time your whole genome is copied to make a new cell, you might end up with six new mutations. And each day, your body will make several billion new cells. A lot of the new cells your body makes each day are red blood cells, which won’t have any descendants, but among all your cells, you’re still creating many millions of new mutations in your DNA each day. Sometimes, the mutations are in cells that go on to grow and then divide again, which means that the mistakes pile up – six from the previous generation, six from the new division, and there will be six more soon, until eventually there are hundreds of mistakes!

And, outside your body, just thing about how many living organisms there are – reasonable estimates are in the range of 10 ^ 30, which is a number too mind-bogglingly large for me to really think about – and just how long there has been life on earth – billions of years – so, over all that time, there have been many, many mutations.

If you peer at a bacterium through a microscope, and then later look at your own reflection in a mirror, remember: you share the same ancestors. There’s a single ancient organism – most billion-year-old organisms were never given names, but this one was, and her name is “Luca” – who is great-great-great-grandmother to you both2. And the only reason that you and that contemporary bacterium under the microscope lens don’t look identical is that, as Luca copied her DNA and divided, and then each of those resultant single-celled organisms copied their DNA and divided, again and again through time, they sometimes made mistakes.

New organisms are the result of mistakes. Otherwise every living thing would still be identical to that first living thing. We’d all still look like Luca did, billions of years ago.

#

So, as organisms copy their DNA, they sometimes make mistakes. And those mistakes can sometimes let organisms do new things.

The chloroplasts that let plants harvest energy from sunlight and turn the air into tree trunks or sugar? Those came from mistakes. The hemoglobin that lets you carry oxygen throughout your body? Mistakes. Your magnificent brain? Mistakes!

Obviously, not all mistakes are equally valuable. Most of the time, if you accidentally change the letter in a sequence of DNA, you won’t end up with a sequence that gives an organism’s descendants some marvelous new superpower. Like, with “PET THE DOG NOW,” I can think of a few mistakes that might make for interesting instructions, like “GET THE DOG NOW” or “PET THE HOG NOW,” but it’s much easier to just wreck things, like “PRT THE DOG NOW” (??!).

It’s much easier for random chance to make something worse than to make it better.

But over time, improvement does happen, because the descendants that inherit the exceedingly rare mistakes that made things better … well, those descendants would have better odds to flourish. To eventually have more descendants of their own. And so the (rare!) good mistakes become more common in a population, and the (plentiful!) bad mistakes disappear.

If we look at this process up close, and actually concern ourselves with the well-being of the individual cells involved, the mistakes almost all look tragic. A bacterium split in half and the half that inherited a copy of DNA with a mistake in it, that new bacterium might just flounder and die. And so the lineage with the mistake just ends. Almost all the time, that’s how it happens.

Or, ugh, consider human cancers. Those are caused by mistakes in copying DNA. Which is awful.

It’s only if we zoom waaaaaay out and consider huge numbers of organisms, or huge stretches of time, that we’d be able to see the rare good mistakes spread through a population. We have to be think about timescales of many generations, and callously ignore the well-being of any individual living thing, for the process of evolution to seem like anything other than a horror show.

#

So, evolution is awful. I hope we can all agree on that.

Evolution is real, it’s a simple mathematical process that has happened in the past, and evolution has given us our current world, and evolution is still happening today. Evolution is helping usher in a future full of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and whatever.

No scientist will try to convince you that evolution doesn’t happen – I’m just stating plainly that evolution is the pits.

But understanding how evolution works is essential for understanding our world. Especially now that we’re about to start talking about sex.

(Cue your favorite Salt-N’-Pepa tune .. followed by a horrible record scratch as you realize that we’ll begin by discussing sex among cells & fish & the like. Like, wasn’t that whole essay about earthworm hookups bad enough??!)

#

Imagine we have an organism, and it has some traits, and one particular individual ends up with a mutation that gives it a better version of a trait. Maybe our organism lives in the sea, spends all day swimming around, and the mutant organism can swim extra, extra fast. And then there’s another individual, and it ends up with a mutation, and it develops a fantastic sense of smell, it’s just impeccably good at knowing where food is.

So we have our “swims fast” little buddy, and we have our “finds food” little buddy, but that’s it. The odds that either of their lineages would spontaneously acquire the other beneficial mistake – considering how rarely the DNA copying process makes mistakes at all, and how unlikely it is that a particular mistake would improve a trait – well, let’s just say that we’ll probably be stuck with a lineage of descendants that swims fast toward wherever, and another lineage that swims slowly in the by direction of food. That’s it.

That’s it … until the invention of sex.

Now, you probably think that you know what sex is. Like, maybe you’re thinking, I do not need this pedantic nerd-kins to explain sex TO ME.

You might be thinking this even before you learn that I took sex-ed in Indiana, where my middle school science teacher wheeled a little television out on one of those dinged-up plastic rolly carts and made us all watch the music video for Meatloaf’s “Paradise by the Dashboard Lights.” To the best of my recollection, that was the entirety of our sex-ed lesson.

But right now we’re not discussing what sex is like for humans, but rather what sex is like for organisms.

Those cells that we were discussing before: when they split, each of the new cells receives the entire DNA genome from the original cell. Maybe there are a few (rare) mistakes in the new copy, but, still, it’s the whole set of instructions.

By way of contrast, sex is a form of reproduction where two individual organisms each offer up half the needed genome, and those two halves combine to form a full set of instructions. So the descendant will receive a genome that has never existed before.

Sex is a form of reproduction that makes mistakes more common, and sex intentionally shuffles those mistakes around. Sex allows for all the world’s myriad mistakes to be paired up in potentially new ways.

If our “swims fast” and our “finds food” organisms can have sex, then among their descendants, there might be an organism that swims fast and finds food! And that organism is going to be great at surviving, and growing, and reproducing.

Many generations later, the descendants of that organism, good old “swims fast toward food,” will have inherited the earth.

Seems great, right?

Although, again, this is only great if we zoom out and consider the whole population, over many generations. In the lives of individuals, sex actually makes things worse. Because, yes, when “swims fast” and “finds food” have sex, some of the offspring might be that fabled “swims fast toward food.” But most of the offspring will have no advantages relative to their parents. Some will inherit only the DNA allowing them to swim slowly toward nowhere in particular.

#

The function of sex is to create diversity.

Now, you might think that there are some side benefits – like pleasure, or strengthening social bonds, or helping us sell beer with risque advertisements – but those are only ancillary consequences. The function of sex – why sexual reproduction arose in evolution many times and why most animal, plant, and fungal species still reproduce using sex – is that sex creates diversity, and this sampling of possibility space makes a population more likely to survive changing circumstances.

Sex helps populations, not individuals.

Again, I’m not saying that you, as an individual, don’t think that sex is fun – maybe you do! But sex means that you didn’t inherit a parent’s set of DNA instructions – DNA instructions that were proven to help your parents survive until reproductive age in the circumstances in which they lived – and even if your DNA is great, sex means that if you happen to have kids, they won’t get to inherit your great DNA.

#

Most of the time, sexual reproduction creates individuals who are worse off than if you’d just made a new copy of the parent. If an organism survives long enough to reproduce, its genome had to be pretty good. So why mess with success? Do we really want to shuffle all that DNA, combine it with half the (shuffled!) genome from another individual, and just pray for the best?

There might even be sets of traits that work really well together, and then sex is even more likely to wreck things! Like, maybe an organism with DNA instructions that let it swim fast will also have DNA instructions for a streamlined body shape. And maybe the organism that swims slowly also has DNA instructions for an armored exterior. I can imagine a world in which both those sets of traits are great.

But if those two organisms have sex, they might produce offspring that are slow and streamlined, or potentially fast but constantly wasting energy from trying to lug about all that armor, and maybe both those sets of traits are terrible. By shuffling traits around, sex would make so many of the offspring’s lives worse than their parents’.

But that’s the thing. Sex is worse for individuals. It’s going to be really rare that randomly shuffling traits together will give you a better organism than the one that we know already had what it takes to survive until reproductive age. Seriously, that set of DNA instructions already received the “Biology 101” seal of approval:

“You, dear organism, survived long enough to reproduce! Good one you! Here’s a ribbon!”

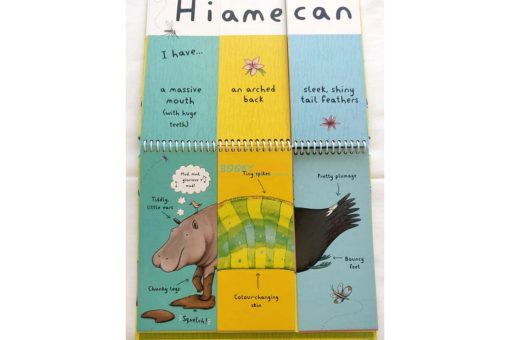

Sex is more likely to create ineffectual mash-ups like those “mixed-up animal” board books, a hodgepodge of traits that might make no sense together.

What sex is good for – so good that sex was invented independently by so many forms of life, and so good that nearly all multicellular life in the world today still reproduces using sex – is only good for populations. Because sex creates diversity. Sex creates a world in which you have your fast streamlined and slow streamlined and slow armored and wanna-be-fast-if-not-for-all-this-armor!!! organisms, all the potential combinations. Even if some combinations are terrible, sex will “sample” them, which sounds cool in mathematics – we’re going to “sample” this dataset – and is tragic in real life, because we’re talking about real living things who are born with unhelpful DNA.

So, sure, most of the time, maybe we think we know which combinations are going to be best. But maybe, just maaaaybe, if the world changes, like if there’s some terrible disaster, and now there’s less food, so only the organisms with slow metabolisms are likely to survive, and maybe the only food to be found is at the bottom of tiny holes in the ocean floor … well, maybe then, only the slow streamlined offspring will survive. Maybe in that one weird set of circumstances, that combination of traits was actually the best.

If there were no sex, then there only would have been the fast streamlined and the slow armored organisms, and that means the whole population would have died off. That would have been the end of the lineage. Extinction.

But in a population with sex, there’s enough diversity that there might be some individuals who can flourish even after circumstances change.

In most generations, the slow streamlined offspring were just eaten by predators. But after the disaster, they might be the only survivors.

#

If the world never changed, then there would probably be no sex. Because the cost of sex is so high.

The cost of diversity is that you’re creating a bunch of offspring that are probably less well-suited than their parents to survive in the world as the world was yesterday. Which is wasteful, right? Better for a parent to just make offspring with exact copies of its DNA. Trying something new might fail, and there’s already a known solution that seems to work!

But the world does change. There’s a gradient of temperatures from the equator to the poles, there’s a daily cycle from day to night, a yearly cycle from summer to winter, new islands that form from volcanic eruptions beneath the sea, massive shifts in climate from one millennium to the next.

Sex helps populations of organisms flourish through all those changes.

#

In any period of stability, organisms might shift back to the old form of reproduction. Making a new organism that has the exact same set of DNA instructions as its parent. Currently in the world, there are fish that do this, and lizards, and snakes. Parthenogenesis. It’s a good solution. When a set of DNA clearly works, why change it?

But these organisms typically live only in environments that appear not to have changed much recently (as in, for the last few million years), and then, when the environment does change, the whole population might go extinct. Because there’s no diversity. There’s no individual who was kind of struggling but is going to be king now that the place where they live is a few degrees colder, or warmer, or a bit saltier or whatever.

So in our changing world, the only populations – where the word “population” means a large group of individuals who all seem similar enough that eventual descendants might be able to receive DNA instructions from any of them, all jumbled together in new ways – almost the only populations that have persisted long enough for us to still see them in the world today, here and now, are the populations that reproduce using sex. Because diversity works. It’s bad for individuals. It’s bad for predictable circumstances. But as soon as the world throws a curveball, that’s when a diverse population is most likely to succeed.

#

Because the function of sex is to create diversity, we’re likely to see diversity in the expressions of biological sex within each population. There’s no way to get that function – the diversity of circulatory systems, or fur length, or adult body mass, all shuffled together because a population has been reproducing using sex – without also having diversity in the phenotypes of sexual expression.

The pursuit of diversity is so valuable for populations that sex exists despite myriad costs. There’s not just the likelihood that offspring will be less good at survival than their parents, but also the chance that the population might include a large number of non-reproductive individuals, like the males in a non-hermaphroditic species.

In biology, the word “male” is defined as an organism in a sexually-reproducing species that makes small gametes. Sperm cells are smaller than egg cells. Human males are individuals who make sperm cells.

In biology, that’s all the word “male” means. It doesn’t have anything to do with adult body size or stereotypical behavior or testosterone levels or parenting commitment. “Male” just indicates the size of the cell that an individual uses to provide its offspring with half a genome.

But just like when we imagined a population of organisms where there were bundled sets of traits like swimming fast & being streamlined, or swimming slowly & being armored, sometimes there are combinations of traits that have worked well together in the past to help organisms survive and reproduce. Sex will continually produce more diversity, because that’s what sex is, a way to sample more of the combinations of traits that organisms in a population might have, but over time, the individuals who had certain stereotypical sets of traits might have been more likely to flourish.

And in that case, there are some neat things that can happen with the actual molecular structure of DNA. Like, the traits that pair well together might end up with their instructions physically near each other on the DNA. Or there might be new mistakes that actually turn into a hierarchical form of instruction, essentially like saying “If the organism has the right DNA instructions to be fast, also use these instructions to make it streamlined; otherwise, make it armored.”

This is a bit like the “If / Then / Else” clauses we use to write computer programs … and biology does it too, with the instructions in our DNA.

I think that’s pretty cool! And it’s roughly what happened in humans. There’s an instruction on the Y chromosome called “SRY,” which stands for “Sex-determining Region of the Y chromosome,” and that DNA instruction, when it’s read off inside a developing body, usually initiates a whole cascade of other instructions that produce the traits we think of as being male, like producing sperm cells, having larger external genitalia, having a deeper voice, being taller, being more risk-prone, being more boastful, etc.

But this cascade of instructions was produced by sex. And new combinations are being produced by sex with every generation. So we should expect the actual manifestations of this to be diverse. We should expect that there will be individuals with other sets of traits. Who are tall, deep-voiced, and risk-averse. Or whatever else. Because that’s what sex does.

The only reason why a population would keep paying the costs to reproduce using sex is that diversity is helpful in times of disaster … and, on Earth, there has always been a new disaster.

Sex is constantly sampling the entire possibility space of all the ways that there could be a human being, and so, even though that hierarchical cascade produces a lot of individuals with two distinct ensembles of traits, sex will produce some individuals who are different. Who might have intermediate traits, or unexpected combinations of the existing traits. Maybe you can imagine future worlds in which those individuals would have an advantage. Or maybe you can’t. But sex will create them anyway. Because that’s what it does. Tinkering, exploring, making new amalgams like you’ve never seen before because, well, what if it turns out to be really great?

#

Categorizing things is easier on our brains. Instead of remembering that a particular friend is six foot three, we just remember that this friend is tall. Which is less taxing for our brains. Everybody does this: me, you, artists, scientists, rabbits. Rabbits look at big shapes and categorize them as predators or not. Scientists categorize things so often that we’ll even categorize bacteria as belonging to a particular species, even though the bacteria reproduce by making copies of themselves (so each one will produce a distinct lineage) and even though bacteria from very different species can transfer DNA instructions between each other (so there’s still gene flow and interwoven lineages of descent even among bacteria that we’d otherwise swear are distinct).

But a “species” isn’t real. “Species” is a word that we use to communicate with each other. Sometimes, the word “species” will help us to think about the world more clearly – if I say that two bacteria belong to the same species, you might anticipate that they’ll have similar molecules on their exteriors, and so they might be recognized by the same antibodies if they infect a person who has prior immunity from a vaccine or a previous infection. Sometimes, the word “species” might cause misunderstandings – if I say that bacteria from one species have an antibiotic resistance gene, you might mistakenly assume that this resistance gene won’t be transferred to a bacteria from a different species. The word might be helpful or not, depending on what conversation we’re having.

Similarly, the word “male” is a tool for human communication – the word evokes a set of ideas, but the word itself doesn’t correspond exactly to anything that actually exists in the world. In some organisms, two individuals that are capable of reproducing with each other using sex make gametes that are both the same size: which of those two individuals should we call male?

And in humans, although our long history as a successful lineage has resulted in particular sets of traits commonly being expressed together, our equally long history as a lineage that’s been using sex to mix up those traits has given us a population where some individuals defy easy categorization. Which isn’t a new understanding of the world. The Talmud, a compendium of ancient Jewish learning, listed about a half dozen variations of biological sex. When people have paid attention to these differences, they’ve noticed that there’s a range.

No one knows exactly how common the major deviations are. Some researchers have made estimates based on how frequently medical doctors performed surgery on newborns who could not easily be categorized as male or female at birth. But also, many traits can’t be identified at that age: I’ve yet to encounter a deep-voiced, tall, risk-prone, boastful newborn.

We do know that the human system of sex determination – essentially, a set of DNA instructions on a single chromosome that tells cells to begin following a bunch of other DNA instructions that are scattered throughout the genome in order to create a male brain and body – that system is only one of many ways that these cascades of instructions can be triggered in animals. In some animals, temperature initiates the cascade – a warmer egg is more likely to be assigned male at birth. In still others, sexual development is determined by social and environmental cues, and new sexual development can happen at any age, with the creature able to develop a new type of brain and body at almost any time during adulthood.

And in all those various species, because their sexual development was created by sex, and because sex is a process that shuffles DNA to generate diversity, there are many different outcomes. Sometimes these different outcomes are difficult to recognize at a glance – when I see a fruit fly hovering in my kitchen, I never know whether it’s male or female. Sometimes, the differences are easier to spot, like in the birds or butterflies with distinct patterns of color between males and females – at a glance, you can recognize individuals who display a separate sex on each side of the body.

#

In modern parlance, the word “queer” is often used for relatively uncommon phenomena that don’t fit into the binary categories that describe the majority of cases. Among humans, the terms “male” and “female” have often seemed like reasonably good descriptors for a lot of people, like at least eighty percent of the population, if not more (although there is a chance that these categorizations feel like they fit well for fewer people of more recent generations, and it seems likely that there are both social and environmental reasons for this change). But for some people, the shorthand assumptions about a person who is “male” – that this person should have a certain sort of appearance, a certain sort of behaviors, and feel attracted only to people who are “female”3 – don’t fit.

And that’s exactly what we’d expect.

Because we were created by sex – for over a billion years, for waaaay more than a billion generations, the lineage that led to us has been reproducing using sex – our population, the human population, has diversity. And because we are still reproducing using sex, we are creating new diversity all the time. Sex is still shuffling all those DNA instructions around, exploring new ways of being with every generation.

Sometime around five or ten million years ago, our ancestors still had twenty-four types of chromosomes. Nearly all other large primates still do. But those ancestors were reproducing with sex, a system that by design muddles with our chromosomes. An individual was born with two of those chromosomes glommed together. Lo and behold, that individual flourished. Now nearly all humans have only twenty-three types of chromosomes.

There are very few differences between the actual letters in your DNA instructions and the DNA instructions that create a chimpanzee, but there are significant differences in how those instructions are arranged.

And all of this diversity has helped humans to survive. To thrive. Because the world has changed a lot. During the past few million years, when creatures who were recognizably human first began to walk the planet, average global temperatures have at times been radically different from what they are now. New lakes and rivers have formed and vanished. Bridges between the continents appeared, then disappeared. Humans spread from their original home in the grasslands bordering tropical forests to every earthly environment, from frigid tundras to scorching deserts.

If there were only A SINGLE WAY for humans to be – or even A SINGLE WAY for a human male to be – then we wouldn’t be here today.

.

.

.

- Here, I’ve said that when “a cell” copies DNA, it will make no more than 1 mistake per 10 ^ 9 letters. This is true for most of the cells in your body, but the frequency of mistakes is different for different organisms. (This number comes from Moore et al., “The mutational landscape of human somatic and germline cells,” Nature 2021.) Some organisms, like most contemporary bacteria, replicate their DNA in ways that create more frequent mistakes. And, although viruses are not alive according to the standard definitions used in biology, perhaps you remember that at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, researchers felt relieved that the DNA copying machinery in Covid-19 makes fewer mistakes than the DNA copying machinery in influenza. The influenza virus mutates faster, which is a major reason why it has caused so many annual deaths for so many years — influenza keeps changing in ways that evade our immune systems. ↩︎

- Technically, her name is spelled in all caps, LUCA, because it’s an acronym for “Last Universal Common Ancestor.” And, weirdly, even though she is billions of years old, she is also still alive, as I’ve written about previously. The cells in your body make you, but also – they are LUCA, still copying her DNA and splitting into two cells, each of which is her. ↩︎

- Many stereotypical traits result from the interplay between culture and biology, though. In some cultures, the epitome of male behavior involves great outbursts and demonstrations of feeling, in other cultures, a stereotypical male is seen as extremely withdrawn and controlled. Sexual attraction has a similar mix of biological and cultural influences; in contrast with contemporary American culture, prevailing norms in the Roman empire, in feudal Japan, in ancient Greece, and in several Indigenous South American cultures taught that “male” behavior was to sexually dominate people of lower status, so a man who felt attracted to other men would be seen as more dominant and more masculine than a man who could only dominate women. And among animals generally, there is reason to suspect that bisexuality or pansexuality would be more common than strict heterosexuality, since the cost of passing up an opportunity to mate with a fertile partner is high — that animal would have fewer descendants — but the cost of additional matings with non-fertile partners — whether because the partner was encountered at the wrong time in their reproductive cycle, or the partner is the wrong biological sex, or the partner is the wrong species — is often relatively low, since mating might be brief and sperm cells are not particularly expensive to make. ↩︎